Willingness in a Day of God’s Power

We have seen how radical the Moravian movement was in terms of their willingness to go to far off places and faithfully serve people with the gospel.

This came about, by their own admission, as a result of the move of the Holy Spirit amongst them in 1727. We shall see in later posts how this same dynamic operated in England and America, a move of God so powerful that it’s been called ‘The Great Awakening’.

Crossing Racial and Cultural Barriers

In this post we’ll look at how this impulse for mission enabled them to cross cultural and racial boundaries (albeit imperfectly) and how they reached out towards the slave communities of the West Indies (then under Danish rule).

Mark Noll, in the slow moving but fact-filled work, ‘The Rise of Evangelicalism’ takes up the story:

‘In the early 1730’s a black servant at the court of the King of Denmark, by the name of Anton, was brought to Herrnhut by Count Zinzendorf so that he could plea for volunteers willing to go to his native St. Thomas (Virgin Islands).

Anton hoped in particular that they could share the gospel message with his enslaved sister Anna.

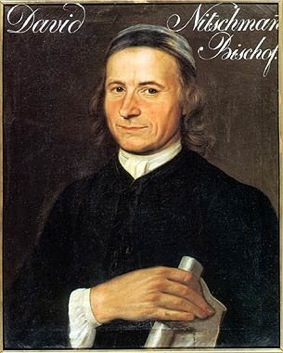

In response, Johann Leonhard Dober and David Nitschmann left Germany for St. Thomas, where the work they began in 1732 produced almost immediate results.’ (Mark Noll, The Rise of Evangelicalism, IVP, p.161-2)

Apostolic Passion

It was in preparation for this work that the servant-hearted Dober expressed his willingness to give all to reach the slaves with the gospel, even if it meant his own enslavement. The motivation of his heart was expressed with apostolic simplicity: ‘on the island there still are souls who cannot believe because they have not heard.’ (Christian History Magazine, Issue 1)

The Moravian missionaries followed in the footsteps of the Anglicans, who had arrived earlier, but the local people preferred the Moravian message.

Noll writes, ‘Anglican Christianity remained resolutely hierarchical, made much of status and hereditary roles…[and] maintained sharp racial divisions.’

By contrast the Moravians seemed to be offering a far more inclusive style of church life. ‘They encouraged blacks to sing with whites, preached spiritual equality before God and welcomed the expression of religious emotion…’

‘So radical were the Moravians for their time that one of the early workers in St Thomas actually took a bride [of mixed race], a step that brought down the wrath of the island’s white planters…’ (ibid. p.162)

The Moravians also encouraged black preachers (or, ‘exhorters’) to emerge and serve in leadership positions in both small groups and congregations.

When they began planting churches in Jamaica (1754), Barbados (1765) and Antigua (1756) they were permitted to operate by the planters, but under close scrutiny. Noll adds, ‘ On Antigua there was special response, with over 11,000 gathered in Moravian churches by the end of the century.’ (ibid. p.162)

Did Moravian Missionaries really sell themselves into Slavery?

In my research on the Moravians I have yet to find an instance where Moravian missionaries voluntarily sold themselves into slavery, although this is often claimed.

Some assert that Dober and Nitschmann did this but produce no supporting evidence or sources to support the claim. As already noted, Dober expressed a willingness to become a slave if that were necessary, but I would be grateful to anyone who actually has primary or reliable secondary sources for the claim that any Moravian Missionary actually did so.

The Spirit and the Needs of the World

Nevertheless, once again we can see that a move of the Holy Spirit amongst Christians resulted in life long sacrifices for the sake of bringing the gospel to others. These Moravian community didn’t enthusiastically embark on a kind of self-centred quest purely for further experiences of the Spirit (although we must assume they enjoyed many such glorious times in the context of mission).

They certainly had their faults, weaknesses and idiosyncrasies, but were determined to bring the gospel to others.

They were filled with the power of the Spirit and set the course of their lives towards connecting with those outside the church, in order to bring them to Jesus Christ.

May God do the same with us in our day, for our generation.

Next time we’ll see how the Moravians’ church planting efforts improved the economy of the host societies. Click here

© 2009 Lex Loizides

It is wonderful to see how this insular community became so outwardly focused. I think you are right about the experiences in the Spirit not ending after their “Pentecost.” I don’t think the missionary advance would have happened with out the continued prayers (100 years) and continued infilling of the Spirit.

Concerning evidence for Moravian missionaries selling themselves into slavery: I happen to have an original copy of the 1821 book “Die Gedenktage der erneuerten Brüderkirche” (The Memorial Days of the Renewed Church of the Brethren), which journals the main events in the history of the Moravian Church, and just looked something up. You can find it here on Google Books (sorry, only German and broken letter typeface):

http://books.google.com/books?id=NIYsAAAAYAAJ&printsec=titlepage&hl=en

On page 161, the aforementioned slave Anton explains that, due to the work load, it would be almost impossible to spend time with slaves in order to teach them the Gospel unless one would become a slave oneself and do so while working. Leonhard Dober and another young man then declared that they were willing to sacrifice their lives in service for the Savior and become slaves even if they would only win one soul.

However, having arrived in Copenhagen, a Mr. von Pless (Oberkammerherr von Pleß) asks them how they would sustain themselves on St. Thomas (page 167). When they answer that they want to work as slaves, he informs them that this is impossible and will not be permitted. David Nitschmann, who was a carpenter, ended up providing the livelihood for both until he returned to his family in Germany in April of 1733. Leonhard Dober, a potter, was hired by the governor to watch over his house, and later earned his living by various jobs (see pages 176 ff.).

Still, as you said, their willingness is what counts – and it was plenty of sacrifice regardless.

thanks for this info, I am doing an essay for my degree at redcliffe college gloucester on early moravian mission and have found the piece on Dober & Nitschmann really useful. many thanks